Author’s note: For spooky, maximum effect, it is best to read this article with the lights off and holding a flashlight under your chin.

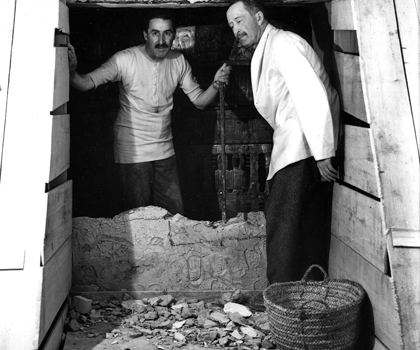

One fateful day in 1922, British archaeologist Howard Carter discovered the nearly intact tomb of boy pharaoh Tutankhamen in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings…or did he? Yeah, he did. With the help of his wealthy aristocratic buddy George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon, Carter excavated the tomb and…unleashed a mummy curse?

Well, nothing awesome happened, such as the awakening of an evil mummy with deadly, fantastical powers. But a mere one year later, Carter was pushing daisies. The cause of death: a mosquito bite, which became infected after he cut himself shaving, resulting in fatal blood poisoning…or was it? Yeah, it was. Pretty mundane stuff. If you want to find something to blame it on, it was the lack of scientific knowledge about treating infected wounds. If you also consider he was suffering from poor health long before his visit to King Tut’s tomb, there’s nothing mysterious about the fact that he died.

But what about the other 44 Westerners (the “curse” was said to not affect the locals) who were reported to have been in Egypt when the tomb was examined? A 2002 study by the British Medical Journal calculated the mean age of death of the folks who were around the tomb…and you will be absolutely shocked at what they discovered! Or not. They found nothing unusual. Nobody was more likely to have died as a result of being exposed to any supposed curse. Noted supernatural debunker James Randi found that those who in theory should have been cursed went on to live another 23 years on average.

Consider this: if anybody should have dropped dead real quick, you’d think it would have been Carter, right? After all, not only was he the one who discovered and physically opened the sarcophagus, he actually removed the mummy. Tut should have been shaking with rage. Yet, Carter lived another 16 years, dying at the not-so-tender age of 64. Herbert’s daughter, Lady Evelyn Beauchamp, who was also present at the opening of Tut’s tomb, lived another 57 years after the event, dying at 78 of natural causes. Or was it a mummy curse that for some reason decided to let her live a rich, full life and then waited half a century to finally do her in? Boy, it’s really difficult to tell, isn’t it?

So here’s our spicy hot take on the Curse of Tutankhamun: Yeah, nope. So what gives? How did the rumor of the curse spread? One of the culprits was journalistic sensationalism. The newspapers at the time weren’t merely content with the discovery of King Tut. Reporting things at face value from a scientific point of view wasn’t enough. There had to be more to it. It needed to be perceived as daring and dangerous. Surely the ancient Egyptian pharaohs had responded by unleashing a terrible plague.

It didn’t help that popular contemporaries such as Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle — who believed in the supernatural, witchcraft and a whole lot of other nonsense — responded in a New York Times article that there were “many malevolent spirits” and that one of them might very well have signed Herbert’s death warrant. When one of the members of the excavation party got into a minor traffic accident in 1970, the tabloids teased the idea that it had something to do with the mummy curse because of course they did!

Other influences were movies and fictional books written about the topic. In the aftermath of the discovery, writers were riding the King Tut wave by cranking out stories about cursed mummies and such. Movies such as The Mummy’s Curse captivated the audience’s imagination. But even several decades before the discovery of Tut’s tomb, writers were planting thoughts into the public’s collective head.

For instance, Louisa May Alcott, the author of Little Women and its zany, non-existent sequel Little Women 2: Back and Smaller Than Ever had published a short story in 1869 titled “Lost in a Pyramid; or, The Mummy’s Curse.” But, alas, arguing that a mummy curse exists based on the imagination of writers is like trying to claim vampires are an actual thing because of Twilight.

Of course, it isn’t to suggest artifacts found in the tomb weren’t intriguing. For instance, one of the items recovered was a dagger made of meteorite iron. This can only mean one thing: it must be the work of aliens and/or ancient astronauts. Stay tuned. Perchance some day we’ll write an awe-inspiring article about that theory!